Tag Archives: marius watz

Computer art is an art form in which computers play a role in the process or final product, such as display of artwork. Generative art is at the same time more specific and more encompassing than computer art. Generative art refers to art that in whole or part has been created with the use of an autonomous system. The autonomous system can be a computer, but more broadly an autonomous system is non-human and can independently determine features of an artwork that would otherwise require decisions to be made directly by an artist. In many cases, the artist, or human creator, can claim that the generative system represents their own artistic idea. There are, however, cases in which the system takes on the role of creator entirely.

What is Generative Art?

The late 1950s saw artists and designers begin to experiment with mechanical devices and analog computers. This served as a precursor to the work of the early digital pioneers who would follow in the 1960s. Interestingly enough these early digital pioneers were not artists or designers but engineers and scientists, as they had access to more powerful computing resources at university scientific research labs. A. Michael Doll, an engineer, and professor at the University of Southern California, was the first person to program a digital computer solely for artistic purposes. His later computer generated patterns simulated the visual effects of paintings by artists such as Piet Mondrian and Bridget Riley.

One of the challenges faced by early generative artists using computers was the limitation of output devices. The primary source in operation at the time was the plotter, a mechanical device that holds a pen or brush with its movements controlled by a computer. The computer guides the pen or brush across the drawing surface or alternately moves the paper underneath, according to the instructions programmed. The plotter was a linear output device, with shading only possible through crosshatching. This resulted in much of the early output of generative art focusing on geometric forms and structures as opposed to more fluid content. The pure visual form was prized above content by early practitioners as they considered the computer an autonomous machine that would enable them to carry out their visual experiments in an objective manner. Plotter drawings were typically black on white paper and as such most of the early work produced was black and white, even after printers began to be used. One of the first artists to produce plotter drawings in color was Frieder Nake.

Popular Names in Generative Art

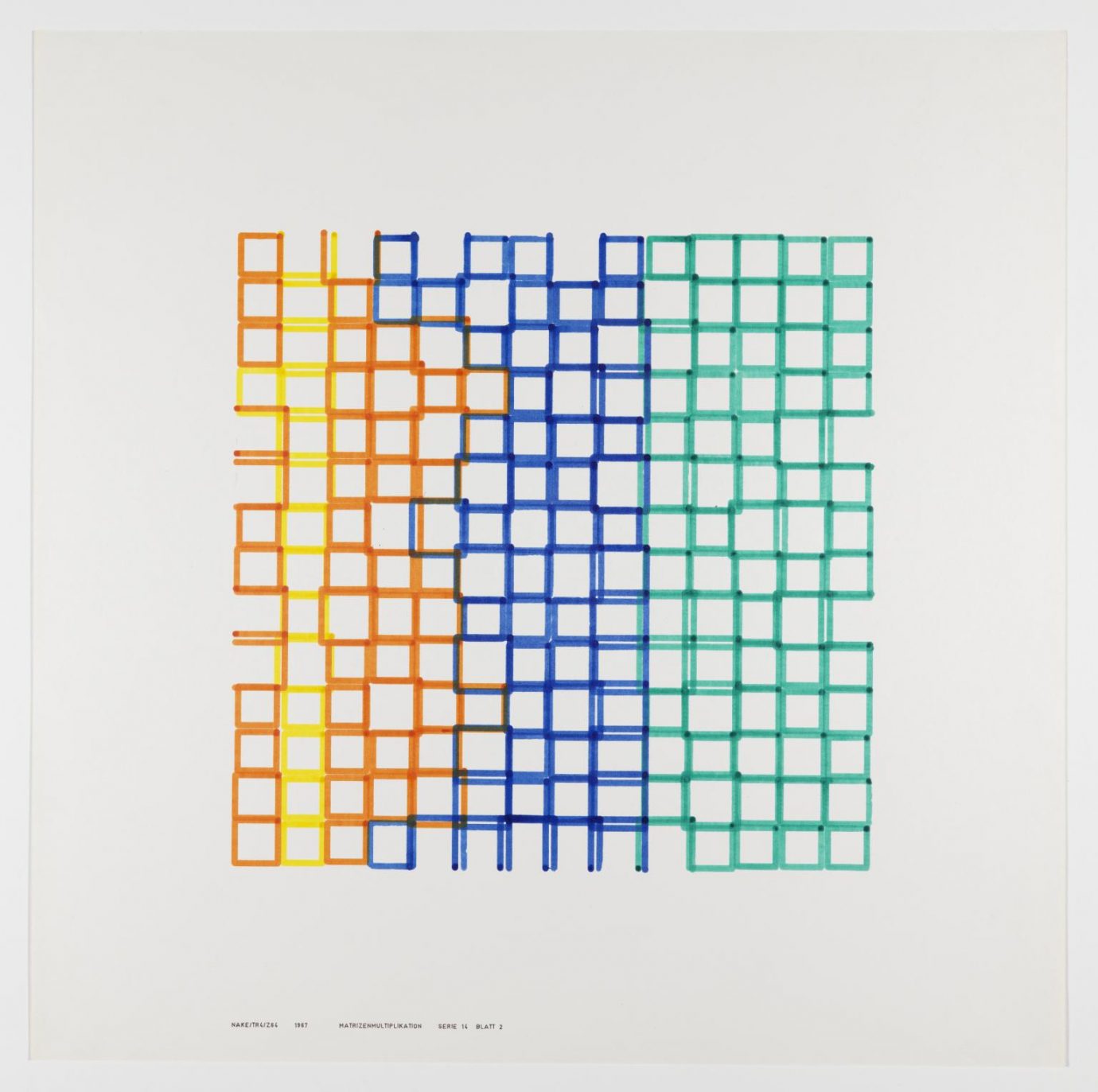

In addition to being a pioneer of computer art Frieder Nake is also a mathematician and computer scientist. Nake was one of the first to exhibit computer art, displaying his work at Galerie Wendell Niedlich in Stuttgart. While a few of Nake’s works were limited edition silkscreen prints, the majority of his work was in the medium of China ink on paper, carried out by a flatbed high precision plotter, the Zuse Graphomat Z64. Nake participated in important group exhibitions in the 1960s and 1970s and his book Ästhetik als Informationsverarbeitung (1974) was one of the first to study connections between aesthetics, computing and information theory, and has become a seminal work for the multidisciplinary area of digital media.

Another early proponent of generative art from a scientific background was Herbert Franke. Having studied subjects as diverse as physics, mathematics, chemistry, psychology and philosophy, Frank received his doctorate in theoretical physics in 1950 for a dissertation he wrote about electron optics. In this capacity, Franke experimented with computer art, and from 1973 to 1997 he lectured a course entitled Cybernetical Aesthetic at Munich University. The course was later renamed Computer Graphics – Computer Art. In 1979 Franke was a founding member of Ars Electronica, a cultural, educational, and scientific institute active in the field of new media art located in Linz.

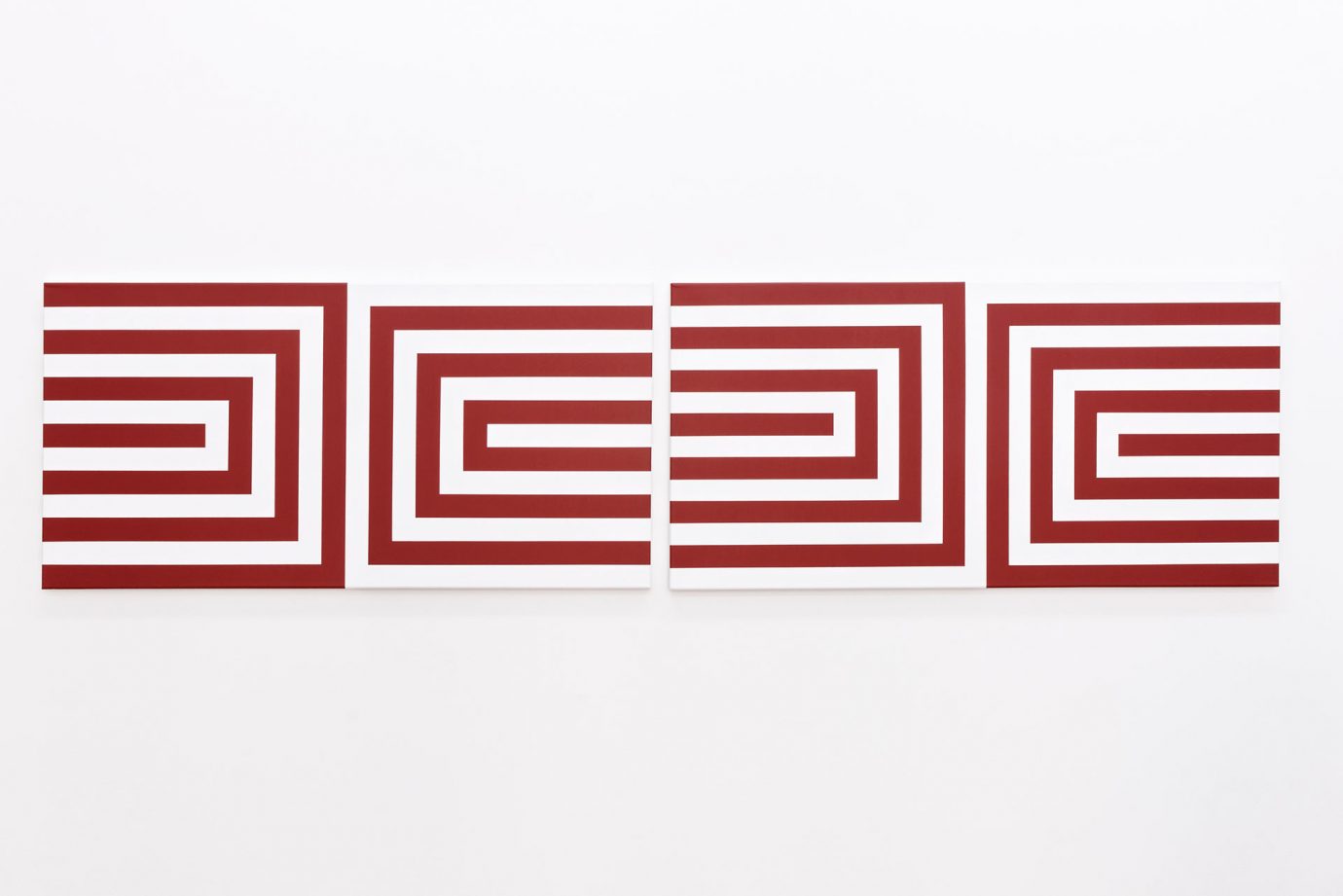

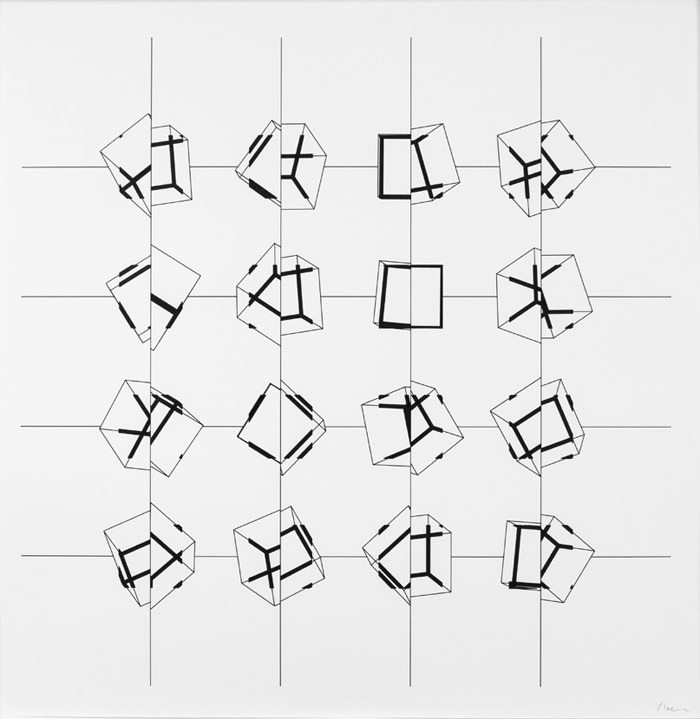

Though the majority of early generative artists were of scientific backgrounds, this was not exclusively the case. Vera Molnar trained as a traditional artist at the Budapest College of Fine Arts. She found her style naturally gravitate to the non-representational, and she experiments with systematically determined abstract geometrical painting as early as the 1940s. After establishing the research group Art et Informatique, which investigated the relationship between art and computing in the 1960s Molnar set out to learn Fortran and Basic, two early programming languages and gained access to a computer at a research lab in Paris where she made computer graphic drawings with a plotter. Another pioneer of digital art that came from a fine art background was Manfred Mohr. Mohr, a graduate of the École des Beaux Arts, was an action painter of the abstract expressionist school who began experimenting with algorithmic art in 1969. His early computer works were based on drawings he had formerly done with a strong emphasis on rhythm and repetition.

Rise of Conceptualism

Simultaneously to the rise of computer art, a more encompassing art movement was coming to the fore: conceptualism was a movement that prized ideas above formal or visual components of artworks. Rather than being a tightly cohesive movement, conceptualism was an amalgamation of various tendencies and took on many forms. From the mid-1960s through to the mid-1970s conceptual artists produced works that completely rejected standard ideas of art of the time. Their primary claim – that the articulation of an artistic idea suffices as a work of art – implied that traditional concerns such as aesthetics expression, technique, and marketability were all irrelevant standards by which to judge an artwork.

Famous Artists in Conceptualism

One artist working in the conceptual vein was Sol LeWitt. LeWitt came to fame in the mid-1960s for his wall drawings, which were essentially the end result of a preconceived set of instructions or simple diagrams for two-dimensional works drawn directly on to walls. The line drawings were purely the result of varying permutations of systems of changing combinations. The parameters of these were chosen by LeWitt himself, and many times the permutations had a systematic ordering about them.

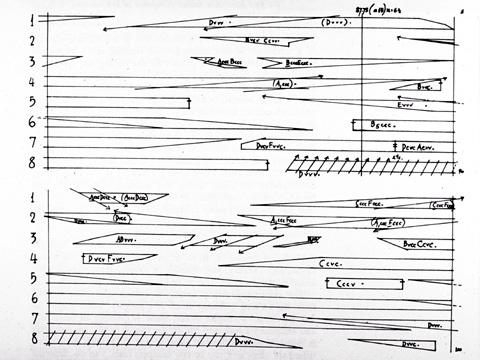

John Cage, arguably one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, was another artistic proponent of conceptualism. He is perhaps best know for his composition entitled 4’33’’, in which musicians who present the work do nothing aside from being present for the duration specified in the title – the work takes place in the absence of deliberate noise, but not in silence. The content of the work is rather the sounds of the environment heard by the audience during the performance. Cage was a pioneer of chance controlled music. Influenced by Eastern texts on decision-making tools in the 1950s, which he employed in his work, aleatoric or chance-controlled music remained his standard composition method for the remainder of his life.

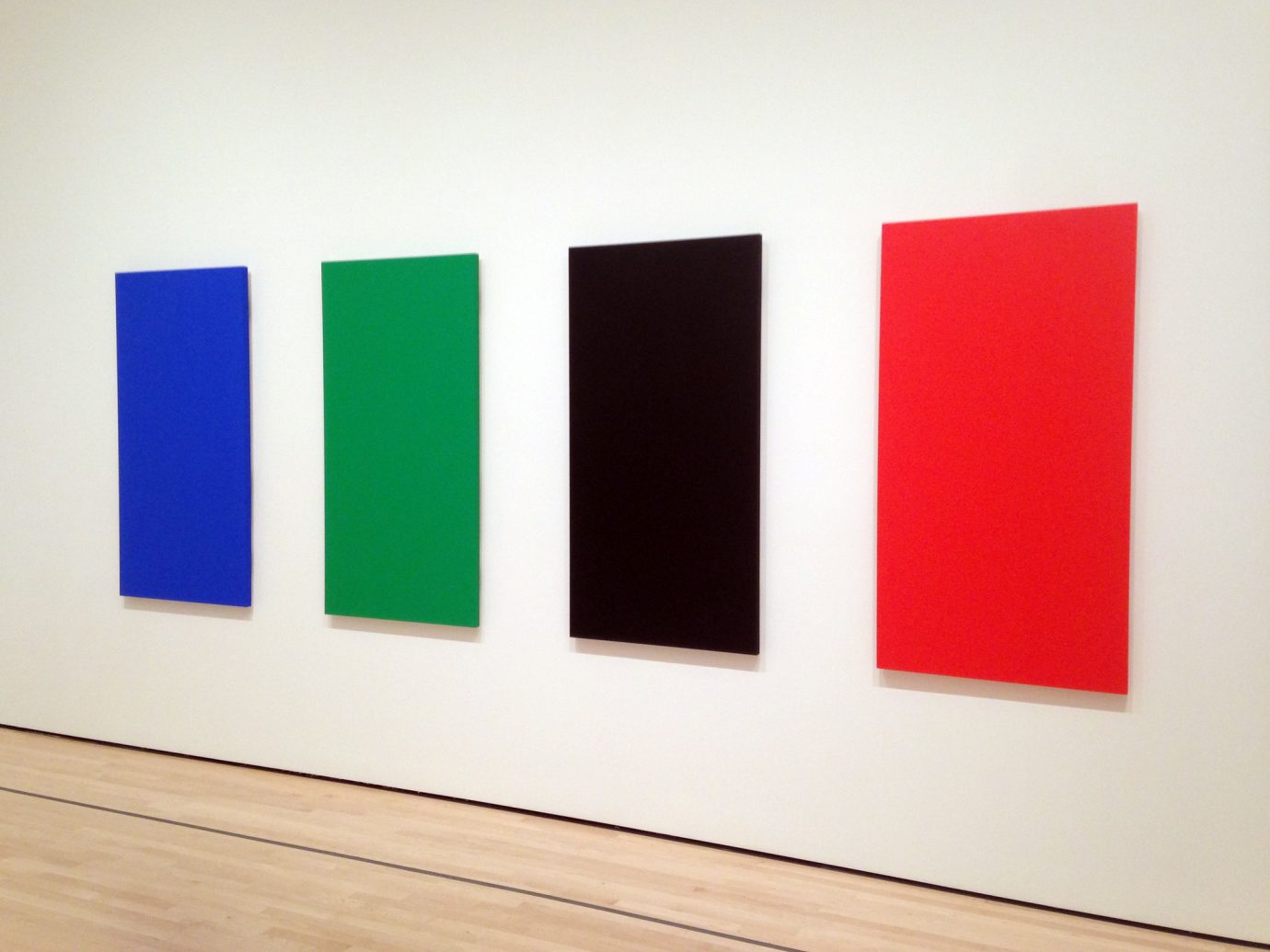

Ellsworth Kelly’s contribution to conceptualism was his persistent inquiry into the dynamic relationship between shape, form, and color. He was one of the first artists to works with irregularly shaped canvases and his later work in layered reliefs and flat sculpture would further challenge accepted notions of space. Kelly’s intention was for viewers to experience his work with instinctive physical responses to the works’ structure, color, and surrounding space rather than with contextual or interpretive analysis. He encouraged bodily participation between the viewer and the artwork, by presenting bold, contrasting colors, free of gestural brushstrokes or recognizable imagery.

Modernization of Generative Art

It was during the 1970s that generative art began to look beyond the computer labs in which it was being practiced and out towards the greater art world. The term soon came to be used to describe geometric abstract art where simple elements were repeated, transformed or varied to generate more complex forms. In so doing the work of Sol LeWitt, John Cage and Ellsworth Kelly became, in a sense, generative art. The broadening of the definition of generative art was not only happening from inside the computer labs but from inside fine art institutions too. In 1970 the School of the Art Institute of Chicago created a department entitled Generative Systems, which focused on art practices using new technologies for the capture, inter-machine transfer, printing and transmission of images. Theorists began placing their own parameters on what generative art was. In 1988, one theorist, Henry Clauser, identified the aspect of systemic autonomy as a critical element in generative art, highlighting that process (or structuring) and change (or transformation) are among generative arts most defining features, and that these features and the actual term ‘generative’ imply dynamic development and motion. As ways of thinking about generative art changed, the practice of generative art changed and a new wave of artists came about bringing with them fresh ideas and new modes of expression.

Next Generation Trendsetters in Generative Art

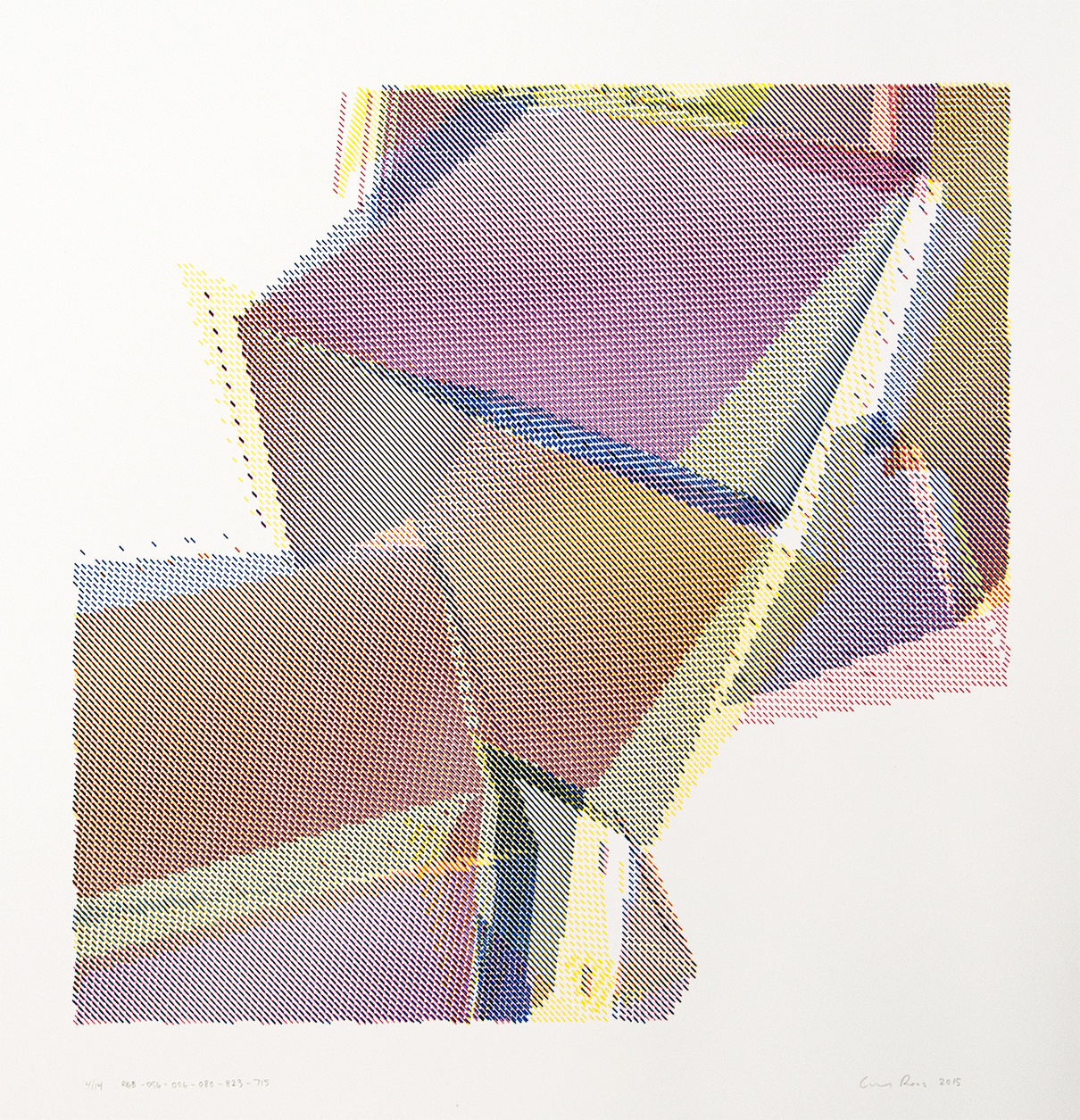

Casey Reas is one of the new waves of artists whose conceptual, process-focused and minimal artworks explore ideas through the contemporary lens of software. The images he creates derive from short software-based instructions. These are expressed in different media including natural language, computer code, and digital simulations, resulting in both static and dynamic images. Each iteration reveals a differing perspective on the process and combines with others to produce continually evolving visual traces. Casey Reas is perhaps best to know for having founded, along with Ben Fry in 2001, the Process programming language. The process began as an open source programming language based on Java to assist the visual design and electronic arts communities to learn the basics of computer programming in a visual context. It is still widely used by artists, designers, and educators. Co-founder of Process, Ben Fry’s digital art focuses more on the potential it holds for use in data visualization than as an independent fine art expression of formal quality only. He is widely considered an expert in the field of data visualization.

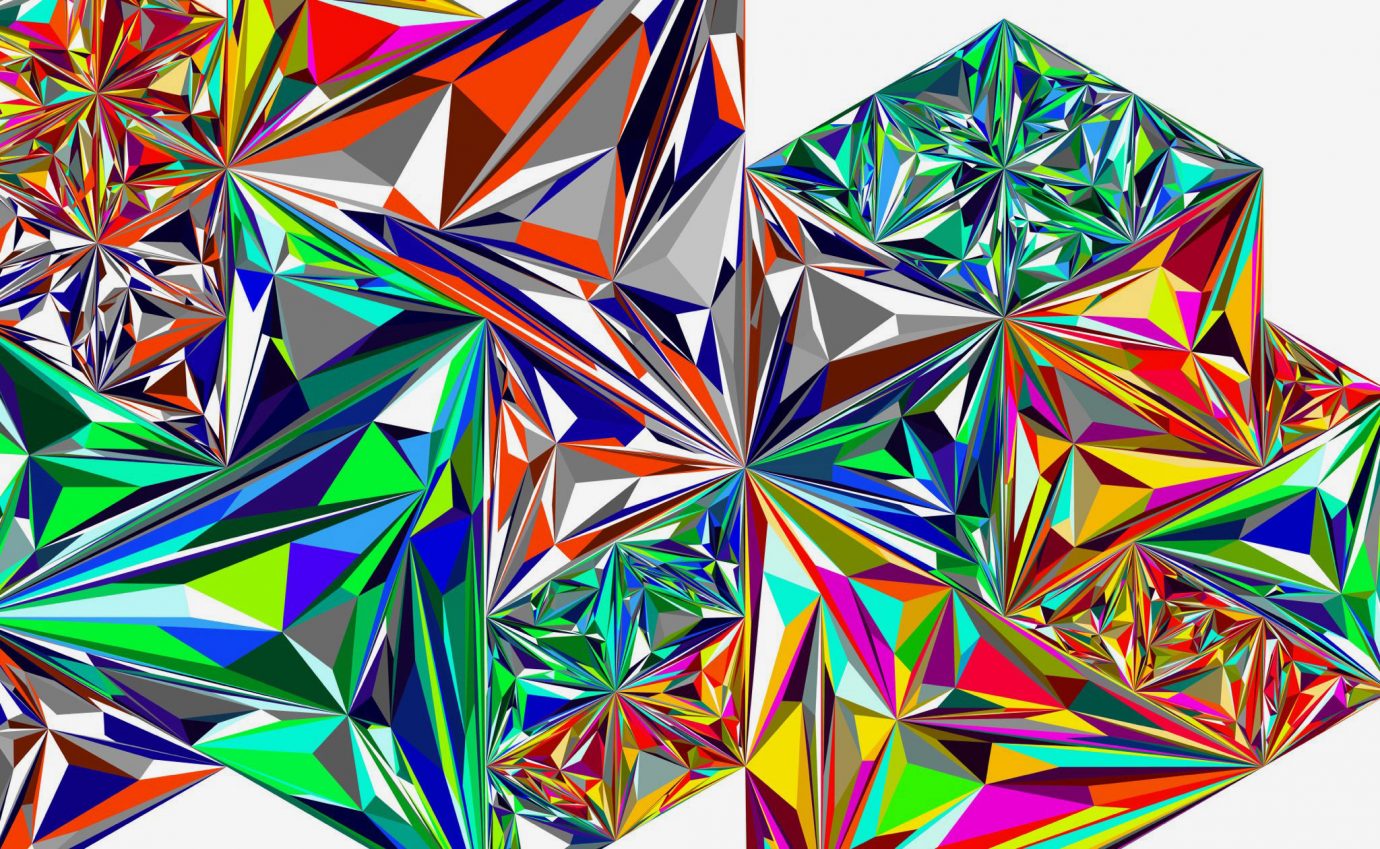

Marius Watz is another new wave artist who produces works within the visual abstraction category through generative software processes. His work focuses on the synthesis of form as the product of parametric behaviours in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional space. His works display hard edged geometrical forms in vivid colours, working in a diverse field of outputs, from pure software work, physical objects produced with digital fabrication technology to public projections. Watz lectures in Interaction Design at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design in addition to giving workshops and lectures on generative systems, parametric design and computational aesthetics. He is represented by DAM Gallery, an affiliate of DAM Berlin (Digital Art Museum Berlin). DAM is an online resource for the history and practice of digital fine art. It informs on historical and contemporary positions chosen by an advisory panel and exhibits the work of leading artists in this field.

A female pioneer of the new wave is LIA, an Austrian artist who has been producing works since 1995. She uses media as diverse as video, performance, installation, software, sculpture, digital projections and applications. Her primary working material is code which she uses to translate a concept into a formal written structure that can then be used to create a machine or program that generates real-time multimedia outputs. The written code element of her work require engineered precision, despite this, her concept is fluid – she treats the translation process between machine and artist as a conversation. LIA continues this conversation until she is satisfied with the machines interpretation, at which point the generative framework is considered finished and the artwork can then develop. Her works typically combine traditional drawing and painting idioms with the aesthetic of digital art, while being characteristically minimalist and conceptual.

A South American component of the new wave is Leonardo Solaas, based in Buenos Aires. His work explores complex systems through computation, interactivity and generative process for both commercial and personal projects. He has used the Process software in experiments in which he explores the subtle differences and undefined boundary territories between art and generative design, calling into use his background in philosophy. Through his work, Solaas has explored various areas of digital cultures in diverse ways such as data visualisation, interface design, net artworks, interactive installation, mobile games, social networks and collaborative creative platforms. His main focus, however lies in the exploration of algorithmic processes for semi-automated production of paintings, drawings, video and sound.

How Generative Art Found its Way to Studios

Towards the turn of the century, much of the focus of generative art practice moved away from artists working independently and towards studios and their production. It is not unlikely that studios would be focussed on the output of a single artist. Despite this, however, studios allow for a more collaborative environment within the practice of generative art, and when it comes to commercial production studios had the added advantage of giving off a more professional flair, much like design agencies, than solo or independent practitioners. One such studio is Field. Field, operating from London, aims to blend physical and digital experiences, connecting audio-visual experiences with photography, sculpture, and film in an attempt to reflect upon how the world is changing through technology. As ever more complex data systems begin to drive our lives, Field’s artistic and design focus is to create new metaphors that help people, brands and institutions better understand these abstract and intangible concepts.

Generative Art Studio ANF in Berlin

Founded in 2008 in Berlin, Studio A N F operates at the intersection of art and technology. Having worked with brands as diverse as Diesel, Audi, Hugo Boss, Samsung and Mercedes-Benz, Studio A N F aims to imbue something of its own aesthetic practice into each of its commercial projects. Through its symbiosis of algorithm and human intervention, Studio A N F has completed projects in a variety of media such as graphics, animation, data visualisation, sculpture and installations in public spaces. Its founder, Andreas Nicolas Fischer is a graduate of the Berlin University of Arts where he studied under professors Ängeslevä and Sauter. Fischer has exhibited at HEK Basel, Kiasma Helsinki, Eyebeam New York, Today Art Museum Beijing, LEAP Berlin, DAM Berlin, Film Museum Vienna, Rua Red Art Centre Dublin and the Southeastern Centre for Contemporary Art in North Carolina in addition to performing alongside the Winston Salem Symphony Orchestra and contributing visuals for the Flying Lotus 2016 tour.

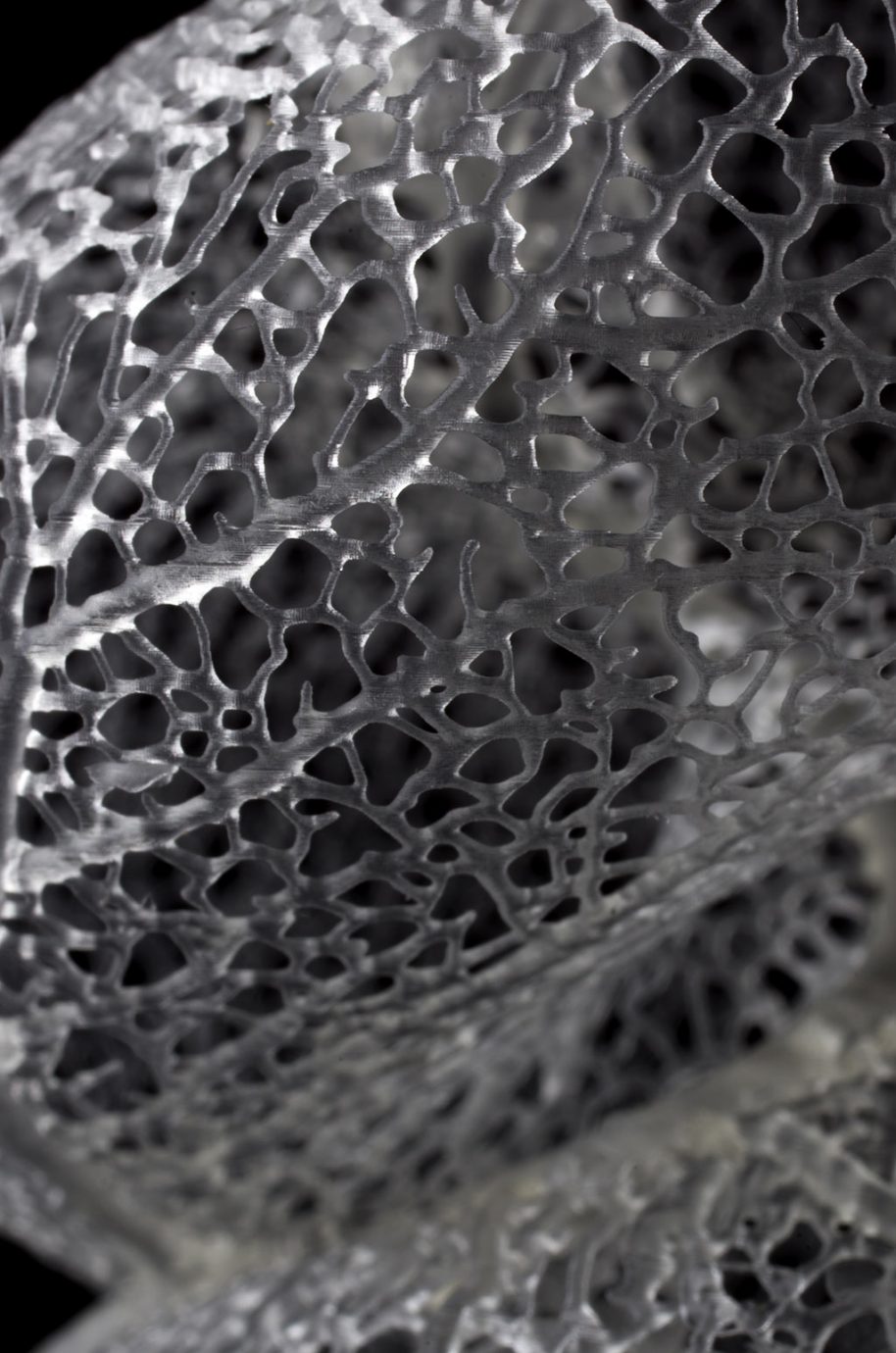

Nervous System is a generative product design studio that creates using a novel process, employing computer simulation to generate designs and digitally fabricate products based in Palenville, New York. Finding their inspiration in natural phenomena, Nervous System writes computer programs based on processes and patterns observable in nature, then uses these programs to create unique and affordable art, jewellery and houseware. Nervous System was founded in 2007 by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg. Rosenkrantz, an artist, designer, and programmer, graduated from MIT in 2005 with degrees in architecture and biology after which she pursued graduate studies in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Following this she founded Nervous System and now also lectures design at MIT. Jesse Louis-Rosenberg is an artist and computer programmer, interested in how simulation techniques can be used in design and in the creation of new kinds of fabrication machines. Jesse studied mathematics at MIT, having previously worked in building modelling and design automation at Gehry Technologies. Through their unique backgrounds Jessica and Jesse have grown Nervous System into what it is today, as it now releases online design applications that enables customers to co-create products in an attempt to make design more accessible. This further allows for endless design variation and customisation. Nervous System has exhibited its work in the Museum of Modern Art, the Cooper- Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Waltz Binaire is another Berlin based studio that designs synthetic realities and moments of engagements in immersive audio-visual experiences, interactive media performances, and digital narratives. Their aim is to translate data into meaningful artworks and convert algorithms into creative patterns by applying generative design and artificial intelligence to their creative process. Their output spans media as diverse as the moving image, mobile platforms, theatres, and unusual stages. Waltz Binaire aims to envision, design and implement new artistic perspectives towards human identity and innovative technology. Waltz Binaire was founded by Christian Mio Loclair, a computer scientist and choreographer.

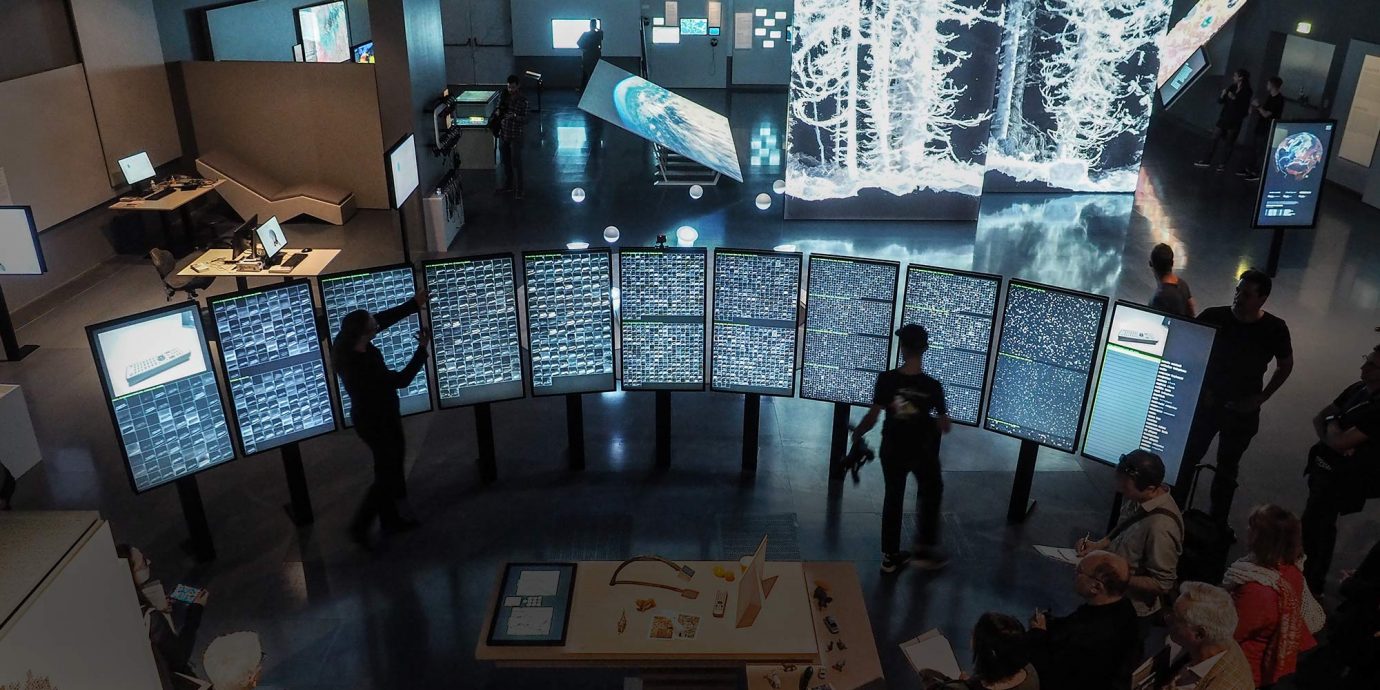

Refik Anadol Studio is the creative studio of Turkish artist Refik Anadol located in Los Angeles, California. Anadol works in the field of site-specific public art, creating parametric data sculptures, live audiovisual performances, and immersive installation pieces. His works explore the space between digital and physical entities by creating a hybrid relationship between architecture and media arts with machine intelligence. Anadol holds a master’s degree in fine art from the University of California specialising in media arts and has won many awards in his field. By embedding media arts into architecture, Anadol questions the possibility of a post digital architectural future in which there are no non-digital realities. Through his work, he thus suggests that all spaces and facades have the potential to be utilised as the media artist’s canvas. Anadol seeks to explore the new challenges that ubiquitous computing imposes on architects, media artists, and engineers such as how our experience of space is changing now that digital objects, ranging from smart phones to urban screens, have colonised our everyday lives, how media technologies have changed our perception of space, and how architecture has embraced these shifting perceptions.

Generative Art – The Next Gen Art

As we see this questioning of the place of generative and computer art in the future due its immersive nature in contemporary society, it is a good time to look to the past, to the roots of generative art. Starting with a handful of scientists in the 1950s, then being taken over by those operating in creative fields, until a harmony is put forth in which science, art, and design can all coexist within the field of generative art at the beginning of the 21st century, as it gains more traction within popular culture. Generative art is certainly set to make further leaps and bounds in its field while spilling over into others as it helps us better understand the world around us.

Text by Kayleen Wrigley